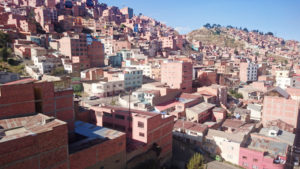

The pure blue sky of La Paz hides a secret spring-like climate behind its weather statistics. On paper, the temperature and rainfall averages look similar to the UK. In reality, the brighter sun, clearer skies and lower humidity provide a radiant heat easier to contain beneath clothing.

The pure blue sky of La Paz hides a secret spring-like climate behind its weather statistics. On paper, the temperature and rainfall averages look similar to the UK. In reality, the brighter sun, clearer skies and lower humidity provide a radiant heat easier to contain beneath clothing.

Plaza Murillo holds the seat of government and a bird feeding station. It’s thick with police, military guards and pigeons. The University staff with their shockingly loud fireworks for protesting for higher wages have intensified the police presence without doing anything about thinning out the pigeons. I have to find my way around this inconvenient obstruction. Mostly, the demos have been peaceful but the longer they continue, the more fractious they get.

Plaza Murillo holds the seat of government and a bird feeding station. It’s thick with police, military guards and pigeons. The University staff with their shockingly loud fireworks for protesting for higher wages have intensified the police presence without doing anything about thinning out the pigeons. I have to find my way around this inconvenient obstruction. Mostly, the demos have been peaceful but the longer they continue, the more fractious they get.

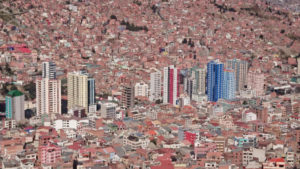

A real gem of La Paz is the ‘Mi Telferico’ Cable car system. There appears to be no practical map available for the system and how it all links together to be able to explore the city. By trial and error, I spend the day moving from one line to another until the whole system has been explored and I have an overview of how the city is covered.

A real gem of La Paz is the ‘Mi Telferico’ Cable car system. There appears to be no practical map available for the system and how it all links together to be able to explore the city. By trial and error, I spend the day moving from one line to another until the whole system has been explored and I have an overview of how the city is covered.

The colour coded cars take you from the heights of El Alto along the canyon of La Paz to Irpavi and across the gorge from one edge to the other. It’s the best way to see the city.

Over the next 5 days, I explore La Paz and take advantage of the relatively fast WiFi at the hostel, reading, writing, studying life; that sort of thing.

Don at the El Condor and the Eagle in Copacabana gave me a tip to find Higher Ground Cafe. I find it easily enough: down Calle Tarija, just up from the purple Teleferico station that’s unfortunately not yet finished construction. Still, it’s not too far to walk down the hill from the hostel. Just harder getting back.

Don at the El Condor and the Eagle in Copacabana gave me a tip to find Higher Ground Cafe. I find it easily enough: down Calle Tarija, just up from the purple Teleferico station that’s unfortunately not yet finished construction. Still, it’s not too far to walk down the hill from the hostel. Just harder getting back.

Calle Tarija is the next street to Gringo Alley (Sagarnaga) and off Linares. It means there are lots of English speaking tourists flocking together. The owner, Mark, is an affable Aussie and his cafe makes for a good place where I can pretend to be a Digital Nomad, a worker from cyberspace.

Gringo Alley: Streets of alpaca-wear stores and fake asian North Face outlets. European coffee drinkers, recharging iPhones, absorbed in the WiFi universe.

I check out some likely locations online to pick up a real paper book -in English- for when Kindle runs out of power. “Spitting Llama,” on Linares just around the corner: now a tour company with cafe. “No Senor, closed maybe two or three years ago.” Another address at 1315 Calle Mercado. Steel shutters. Shrugs from neighbours. Not the first time I find expired businesses still experiencing a zombie life on the world wide web. I give up the search and settle for a coffee.

“El Camino de la Muerte.” A poster of young adventures on mountain bikes. “The worlds most dangerous road,” the poster boasts, at odds with the holiday vibe of the poster.

Wednesday 30th May

Death Road, Groves Road, North Yungas Road, El Camino de la Muerte… the road of many names…

Yes, I was nervous. I don’t like heights…

Since entering my awareness, Bolivia’s ‘Death Road’ had become impossible to ignore: something I could not just ‘not do.’ Like going to Paris and not visiting the Eiffel tower, or going to Cusco and ignoring Machu Picchu. Besides, I had also read that Coroico is at the end of that road at an elevation of 1700 metres. At this latitude, that means warm weather, a summer break from the spring-like chills of the ‘city in the sky.’ All less than a hundred kilometres away.

I loaded up the bike and squeezed its swollen bags through the Hostel doors onto the pale sunlit cobbles on the lane outside. Checking the map, it’s simply a right turn at the crossroads and straight on over the hill to route 3. The cobbled road was steep and the bike steadily rumbled its way upwards before reaching the smooth bleached concrete slopes that became so steep that the bike could no longer grunt its way another inch.

I loaded up the bike and squeezed its swollen bags through the Hostel doors onto the pale sunlit cobbles on the lane outside. Checking the map, it’s simply a right turn at the crossroads and straight on over the hill to route 3. The cobbled road was steep and the bike steadily rumbled its way upwards before reaching the smooth bleached concrete slopes that became so steep that the bike could no longer grunt its way another inch.

I put my feet down squeezing the clutch front brake: not enough traction to hold the bike on the hill on the front wheel alone and slid backwards until I let the clutch out to stall the engine and lock the rear wheel. Steering and propping the back wheel against the curb, I stepped off the bike and started the engine using it to power while I pushed the bike up the hill, collapsing at the next corner to calm my racing heart and suck some oxygen out of the thin air at the corner in a driveway. I’d only gone about 20 metres and round the corner was another 30 metres, just as steep. Beyond that, I could only guess from the angle of the roof gables of the houses continuing up the slope.

I sat panting on the curb watching the cars revving their nuts off and honking at the corners warning of their commitment to their ascent. There was no way I was going to make it to the top with this gearing or engine size in this atmosphere. I’d have to retreat to the main road and head east to where the orange routes were painting themselves on the screen of the sat nav. The big trucks that make it into this basin city have to escape somehow. I’d find out where.

Turning the bike around and rolling downhill on brakes and low gear was easier but no less dangerous. The white concrete was smooth and with barely enough grip. Stopping would be a challenge and my prayers for no traffic were answered, at least until the cobbles where the slope eased off to manageable levels,

Turning the bike around and rolling downhill on brakes and low gear was easier but no less dangerous. The white concrete was smooth and with barely enough grip. Stopping would be a challenge and my prayers for no traffic were answered, at least until the cobbles where the slope eased off to manageable levels,

Continuing the wrong way down the one-way street was an uneventful but useful shortcut, as was turning into the traffic without any clues from the rear of the traffic lights. The other road users didn’t seem to mind and there were no honks of judgement or rebuke and I turned to go with the flow of the minibuses along Calle Sucre.

Using the direction of the sun as my guide brought me halfway out of La Paz on Route 3 before having to stop and check with the sat nav. The outward bound traffic was thinning. It felt like whoever travels to La Paz stays in La Paz.

At the city limits, there was me, a coach and two heavy trucks belching black smoke against the force of gravity; all making our way out of La Paz’s bowl in the sky, from 3700 metres uphill toward La Cumbre Pass at 4600 metres. There was little power available for overtaking and a maximum speed of 40km/h but I took advantage of the unnecessary outward bound speed humps and potholes to maintain my speed by standing on the footpegs to roll over the obstacles and get ahead to breathe diesel free mountain air, while the trucks were forced to slow for the speed humps.

At the city limits, there was me, a coach and two heavy trucks belching black smoke against the force of gravity; all making our way out of La Paz’s bowl in the sky, from 3700 metres uphill toward La Cumbre Pass at 4600 metres. There was little power available for overtaking and a maximum speed of 40km/h but I took advantage of the unnecessary outward bound speed humps and potholes to maintain my speed by standing on the footpegs to roll over the obstacles and get ahead to breathe diesel free mountain air, while the trucks were forced to slow for the speed humps.

The weather was clear and dry with a few wispy clouds wafting over the mountain peaks and tumbling down the mountainside into the valley below. But it was becoming noticeably cooler the higher I got and I was glad of the suns rays for its radiance.

The bleak mountains and stark jagged rocks sheltered the ice in the shade with a hint of tentative plant life clinging for its life onto any surface. 40Kmh, clicking down the gears to try and make some progress only saw the suffocating engine cough at six thousand revs searching the rarified air for precious oxygen. Patience was the only remedy. Entering the cloud base, brought a chill familiar to riding in the British winter. An icy dampness that found its fingers between clothes and skin.

Soon, progress slowly levelled out and then downhill. I was over the pass. This side of the peaks, the clouds were tumbling over the peaks and falling below the cloud base and down the mountainsides and across the road.

Less than two miles in the grey foggy mist. There it was, the entrance to the Death Road. Heralded by a tired and solemn-looking information board and a sign instructing traffic to now pass on the left so the drivers are able to see how soon their wheels will be going over the edge.

Less than two miles in the grey foggy mist. There it was, the entrance to the Death Road. Heralded by a tired and solemn-looking information board and a sign instructing traffic to now pass on the left so the drivers are able to see how soon their wheels will be going over the edge.

I propped the bike on its side stand and walked to the edge of the junction to look down the sunlit valley at the thin yellow ribbon of road slicing its way through the trees and around the mountainsides into the mountain jungle below and to the east.

Watching the road for a few minutes, I could see zero traffic either direction. The Death Road’s new replacement was here behind me continuing into the grey cloud around the other side of the mountain. I saw no traffic here either.

After a quick drink from the water bottle, I slipped my helmet back on and started rolling down the gravel track known as the most dangerous road in the world…